Masonic Manuscripts

There are a number of masonic manuscripts that are important in the study of the emergence of Freemasonry. Most numerous are the Old Charges or Constitutions. These documents outlined a “history” of masonry, tracing its origins to a biblical or classical root, followed by the regulations of the organisation, and the responsibilities of its different grades. More rare are old hand-written copies of ritual, affording a limited understanding of early masonic rites. All of those which pre-date the formation of Grand Lodges are found in Scotland and Ireland, and show such similarity that the Irish rituals are usually assumed to be of Scottish origin. The earliest Minutes of lodges formed before the first Grand Lodge are also located in Scotland. Early records of the first Grand Lodge in 1717 allow an elementary understanding of the immediate pre-Grand Lodge era and some insight into the personalities and events that shaped early-18th-century Freemasonry in Britain.

Other early documentation is included in this page. The Kirkwall Scroll is a hand painted roll of linen, probably used as a floorcloth, now in the care of a lodge in Orkney. Its dating and the meaning of its symbols have generated considerable debate. Early operative documents and the later printed constitutions are briefly covered.

Old Charges

The Old Charges of the masons’ lodges were documents describing the duties of the members, to part of which (the charges) every mason had to swear on admission. For this reason, every lodge had a copy of its charges, occasionally written into the beginning of the minute book, but usually as a separate manuscript roll of parchment. With the coming of Grand Lodges, these were largely superseded by printed constitutions, but the Grand Lodge of All England at York and the few lodges that remained independent in Scotland and Ireland, retained the hand-written charges as their authority to meet as a lodge. Woodford, Hughan, Speth and Gould, all founders of Quatuor Coronati Lodge, and Dr Begemann, a German Freemason, produced much published work in the second half of the nineteenth century, collating, cataloguing and classifying the available material. Since then, aside from the occasional rediscovery of another old document, our knowledge has been little advanced.

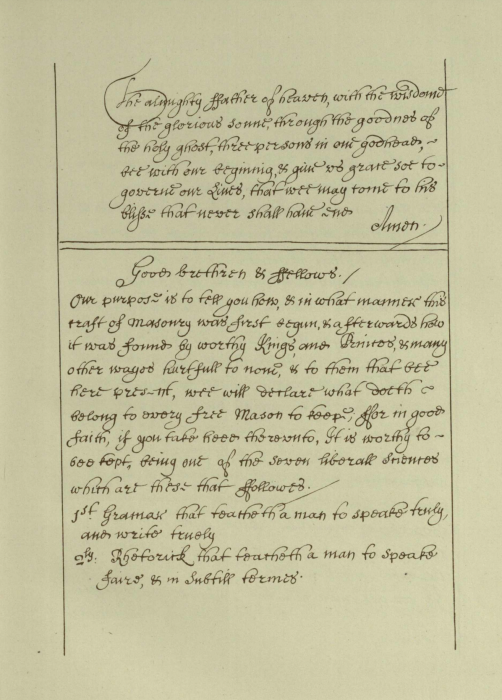

The oldest, the Regius poem, is unique in being set in verse. The rest, of which over a hundred survive, usually have a three part construction. They start with a prayer, invocation of God, or a general declaration, followed by a description of the Seven Liberal Arts (logic, grammar, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy), extolling Geometry above the others. There follows a history of the craft, and how it came to the British Isles, usually culminating in a general assembly of masons during the reign of King Athelstan. The last part consists of the charges or regulations of the lodge (ie by-laws) and the craft of masonry in general, which the members are bound to maintain.

Evolution of the York Legend

The earliest masonic documents are those of their early employers, the church and the state. The first claimed by modern Freemasons as the lineal ancestors of our own Charges relate to the self-organisation of masons as a fraternity with mutual responsibilities. From the reign of Henry VI to the Elizabethan period, that is from about 1425 to 1550, surviving documents show the evolution of a legend of masonry, starting before the flood, and culminating in the re-establishment of the craft of masonry in York during the reign of King Athelstan.

Halliwell Manuscript/Regius Poem (c1390)

The Halliwell Manuscript, also known as the Regius Poem, is the earliest of the Old Charges. It consists of 64 vellum pages of Middle English written in rhyming couplets. In this, it differs from the prose of all the later charges. The poem begins by describing how Euclid “counterfeited geometry” and called it masonry, for the employment of the children of the nobility in Ancient Egypt. It then recounts the spread of the art of geometry in “divers lands.” The document relates how the craft of masonry was brought to England during the reign of King Athelstan (924–939). It tells how all the masons of the land came to the King for direction as to their own good governance and how Athelstan, together with the nobility and landed gentry, forged the fifteen articles and fifteen points for their rule. This is followed by fifteen articles for the master concerning both moral behaviour (do not harbour thieves, do not take bribes, attend church regularly, etc.) and the operation of work on a building site (do not make your masons labour at night, teach apprentices properly, do not take on jobs that you cannot do, etc.). There are then fifteen points for craftsmen which follow a similar pattern. Warnings of punishment for those breaking the ordinances are followed by provision for annual assemblies. There follows the legend of the Four Crowned Martyrs, a series of moral aphorisms, and finally a blessing.

The origins of the Regius are obscure. The manuscript was recorded in various personal inventories as it changed hands until it came into possession of the Royal Library, which was donated to the British Museum in 1757 by King George II to form the nucleus of the present British Library. It came to the attention of Freemasonry much later, this oversight being mainly due to the librarian David Casley, who described it as “a Poem of Moral Duties” when he catalogued it in 1734. It was in the 1838–39 session of the Royal Society that James Halliwell, who was not a Freemason, delivered a paper on “The early History of Freemasonry in England”, based on the Regius, which was published in 1840. The manuscript was dated to 1390, and supported by such authorities as Adolphus Woodford and Hughan. The dating of the manuscripts by the British Museum themselves, to fifty years later was largely side-lined. Hughan also mentions that it was likely written by a priest.

Modern analysis has confirmed the dating to the second quarter of the fifteenth century and placed its likely composition in Shropshire. This dating leads to the hypothesis that the document’s composition and especially its narrative of a royal authority for annual assemblies, was intended as a counterblast to the Scottish Statute of 1425 banning such meetings.

“The Old York Constitutions of 926”, as they are referred to are essentially a translation of the Regius Poem, with the poetry removed:

THE FIFTEEN ARTICLES

- The Master must be steadfast, trusty and true; provide victuals for his men, and pay their wages punctually.

- Every Master shall attend the Grand Lodge when duly summoned, unless he have a good and reasonable excuse.

- No Master shall take an Apprentice for less than seven years.

- The son of a bondman shall not be admitted as an Apprentice, lest, when he is introduced into the Lodge, any of the brethren should be offended.

- A candidate must be without blemish, and have the full and proper use of his limbs; for a maimed man can do the craft no good.

- The Master shall take especial care, in the admission of an Apprentice, that he do his lord no prejudice.

- He shall harbor no thief or thief’s retainer, lest the craft should come to shame.

- If he unknowingly employ an imperfect man, he shall discharge him from the work when his inability is discovered.

- No Master shall undertake a work that he is not able to finish to his lord’s profit and the credit of his Lodge.

- A brother shall not supplant his fellow in the work, unless he be incapable of doing it himself; for then he may lawfully finish it, that pleasure and profit may be the mutual result.

- A Mason shall not be obliged to work after the sun has set in the west.

- Nor shall he decry the work of a brother or fellow, but shall deal honestly and truly by him, under a penalty of not less than ten pounds.

- The Master shall instruct his Apprentice faithfully, and make him a perfect workman.

- He shall teach him all the secrets of his trade.

- And shall guard him against the commission of perjury, and all other offences by which the craft may be brought to shame.

THE FIFTEEN POINTS

- Every Mason shall cultivate brotherly love and the love of God, and frequent holy church.

- The workman shall labor diligently on work days, that he may deserve his holidays.

- Every Apprentice shall keep his Master’s counsel, and not betray the secrets of his Lodge.

- No man shall be false to the craft, or entertain a prejudice against his Master or Fellows.

- Every workman shall receive his wages meekly, and without scruple; and should the Master think proper to dismiss him from the work, he shall have due notice of the same before mid-day.

- If any dispute arise among the brethren, it shall be settled on a holiday, that the work be not neglected, and God’s law fulfilled.

- No Mason shall debauch, or have carnal knowledge of the wife, daughter, or concubine of his Master or Fellows.

- He shall be true to his Master, and a just mediator in all disputes or quarrels.

- The Steward shall provide good cheer against the hour of refreshment, and each Fellow shall punctually defray his share of the reckoning, the Steward rendering a true and correct account.

- If a Mason live amiss, or slander his Brother, so as to bring the craft to shame, he shall have no further maintenance among the brethren, but shall be summoned to the next Grand Lodge; and if he refuse to appear, he shall be expelled.

- If a Brother see his Fellow hewing a stone, and likely to spoil it by unskillful workmanship, he shall teach him to amend it, with fair words and brotherly speeches.

- The General Assembly, or Grand Lodge, shall consist of Masters and Fellows, Lords, Knights and Squires, Mayor and Sheriff, to make new laws, and to confirm old ones when necessary.

- Every Brother shall swear fealty, and if he violate his oath, he shall not be succored or assisted by any of the Fraternity.

- He shall make oath to keep secrets, to be steadfast and true to all the ordinances of the Grand Lodge, to the King and Holy Church, and to all the several Points herein specified.

- And if any Brother break his oath, he shall be committed to prison, and forfeit his goods and chattels to the King.

They conclude with an additional ordinance–alia ordinacio–which declares

That a General Assembly shall be held every year, with the Grand Master at its head, to enforce these regulations, and to make new laws, when it may be expedient to do so, at which all the brethren are competent to be present; and they must renew their O. B. to keep these statutes and constitutions, which have been ordained by King Athelstan, and adopted by the Grand Lodge at York. And this Assembly further directs that, in all ages to come, the existing Grand Lodge shall petition the reigning monarch to confer his sanction on their proceedings.

Cooke Manuscript (c1490)

The ‘Cooke Manuscript’ is the second oldest of the Old Charges or Gothic Constitutions of Freemasonry and the oldest known set of charges to be written in prose. It contains some repetition, but compared to the Regius there is also much new material, much of which is repeated in later constitutions. After an opening thanksgiving prayer, the text enumerates the Seven Liberal Arts, giving precedence to Geometry, which it equates with masonry. There follows the tale of the children of Lamech, expanded from the Book of Genesis. Jabal discovered geometry, and became Cain’s Master Mason. Jubal discovered music, Tubal Cain discovered metallurgy and the art of the smith, while Lamech’s daughter Naamah invented weaving. Discovering the news that the earth would be destroyed either by fire or by flood, they inscribed all their knowledge on two pillars of stone, one that would be impervious to fire and one that would not sink. Generations after the flood, both pillars were discovered, one by Pythagoras, the other by the philosopher Hermes. The seven sciences were then passed down through Nimrod, the architect of the Tower of Babel, to Abraham, who taught them to the Egyptians, including Euclid, who in turn taught masonry to the children of the nobility as an instructive discipline. The craft is then taught to the children of Israel and from the Temple of Solomon, finds its way to France, and thence to Saint Alban’s England. Athelstan now became one of a line of kings actively supporting masonry. His youngest son Æthelwine, is introduced for the first time as leader and mentor of masons. There follow nine articles and nine points and the document finishes in a similar manner to the Regius.

Unlike the majority of the old constitutions, which are written on rolls, the Cooke manuscript is written on sheets of vellum, four and three-eighth inches high and three and three eighth inches broad (112mm x 86mm) bound into a book, still retaining its original oak covers. The manuscript was published by R. Spencer, London, in 1861 when it was edited by Mr. Matthew Cooke, hence the name. In the British Museum’s catalogue it is listed as “Additional M.S. 23,198”, and is now dated to 1450 or thereabouts, although errors in Cooke’s transcription caused it originally to be dated to after 1482. In line 140, And in policronico a cronycle p’yned, Cooke translated the last word as “printed”, causing Hughan to give the earliest date as Caxton’s Polychronicon of 1482. Later retranslation as “proved” justified the earlier dating. Obvious scribal errors indicate that the document is a copy and repetition of part of the stories of Euclid and Athelstan seems to indicate two sources. Speth postulated in 1890, that these sources were much older than the manuscript, a view that remained unchallenged for over a century.

Recent analysis of the Middle English of the document date it to the same period as the writing, around 1450, implying that the source or sources from which it was copied were almost contemporary with the Cooke and contemporary with, or only slightly later than the Regius poem. It was probably composed in the West Midlands, near to the origin of the Regius in Shropshire. The historian Andrew Prescott saw both the Regius and Cooke manuscripts as part of the struggle of mediaeval masons to determine their own pay, particularly after the statute of 1425 banning assemblies of masons. Masons sought to show that their assemblies had royal approval and added the detail that the King’s son had become a mason himself. At line 603 we find: “For of specculatyfe he was a master and he lovyd well masonry and masons. And he bicome a mason hym selfe.“

James Anderson had access to the Cooke manuscript when he produced his 1723 Constitutions. He quotes the final sixty lines in a footnote to his description of the York assembly. The Woodford manuscript, which is a copy of the Cooke, has a note explaining that it was made in 1728 by the Grand Secretary of the Premier Grand Lodge of England, William Reid, for William Cowper, Clerk of the Parliaments, who had also been Grand Secretary.

Dowland Manuscript (c1500)

The Dowland Manuscript was first printed in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1815. The contributor, James Dowland, wrote “For the gratification of your readers, I send you a curious address respecting Freemasonry which not long since came into my possession. It is written on a long roll of parchment, in a very clear hand apparently in the 17th century, and probably was copied from a Mmanuscript of earlier date.” This earlier date is still estimated to be around 1550, making the Dowland the second oldest prose constitutions known. The wages mentioned in the text agree with other manuscripts known to originate in the second half of the sixteenth century. Unfortunately, the original is, quite unbelievably, now lost.

The history is similar to that of the Cooke manuscript. In this case we find that the first charges proceeded from Euclid’s instruction of the sons of the Egyptian Lords. The Master Mason at the construction of the Temple of Solomon is a son of King Hiram of Tyre called Avnon. Again masonry diffuses from the Temple and enters Saint Alban’s England from France. The science suffers in the wars following Alban’s death, but is restored under Athelstan. His son, now named as Edwinne, is the expert geometrician who obtains his father’s charter for an annual assembly of masons, that should be “renewed from Kinge to Kinge”. The assembly under Edwin is, for the first time, identified as having occurred at York. The articles and points are now replaced with a series of charges, in the form of an oath.

The emergence of York, and the appearance of the more modern form of the charges after a century of silence in the documentary record, have been linked by Prescott to government policy in from the second half of the sixteenth century, which allowed wage increases for London masons, while attempting rigid wage control in the North of England.

Grand Lodge No 1 (c1632)

This manuscript inexplicably appears in Hughan’s Old Charges with a date of 1632, which Speth, the next editor, attributed to the terrible handwriting of Rev. Woodford, Hughan’s collaborator. It is the first of the charges to bear a date, which is just discernible as 1583, on 25 December. The document is in the form of a roll of parchment nine feet long and five inches wide, being made up of four pieces pasted at the ends. The United Grand Lodge of England acquired it in 1839 for twenty-five pounds from a Miss Sidall, the great-granddaughter of Thomas Dunckerley’s second wife. The handwriting is compatible with the date of 1583, although the language is older, leading to the belief that it was copied from an original up to a century older. The contents of “Grand Lodge 1” tell the same tale as the Dowland manuscript, with only minor changes. Again, the charges take the form of an oath on a sacred book.

Within this manuscript and the Dowland we find a curious mason called Naymus Grecus (Dowland has Maymus or Mamus Grecus), who had been at the building of Solomon’s Temple and who taught masonry to Charles Martel before he became King of France, thus bringing masonry to Europe. This obvious absurdity has been interpreted by some as a coded reference to Alcuin of York, possibly from a misunderstanding of one of his poems.

Later manuscripts

At this point, the old charges had attained a standard form. What became known as the York Legend had emerged in a form that would survive into Preston’s Illustrations of Freemasonry, (1772) which was still being reprinted in the mid-nineteenth century. The requirement for every new admission to be sworn to the Old Charges on the bible now meant that every lodge should have its own manuscript charges and over a hundred survive from the seventeenth century until the period in the eighteenth when their use died out. Describing them all is beyond the scope of this web site and frankly, unnecessary since differences are only in details, such as occasional clumsy attempts to deal with the absence of Edwin, Athelstan’s son, from any historical record. Differences also occur in the specifics of the charges and the manner of taking the oath. Very few of these manuscripts do have a separate Apprentice Charge. Families of documents have been identified and two systems of classification exist. A few documents do however deserve special attention:

Lansdowne (c1560)

This document was purchased by the British Government as part of a collection amassed by William Petty, Marquis of Lansdowne. It was bundled with papers from William Cecil, a prominent Elizabethan politician who died in 1598 and was assumed to belong to the same period. Analysis of the handwriting places it a hundred years later and later papers have been found in Cecil’s bundle. Lansdowne is still frequently but incorrectly cited as an Elizabethan document.

York No 4 (c1693)

The group of masons calling themselves the Grand Lodge of All England meeting since Time Immemorial in the City of York continued to issue written constitutions to lodges, as their authority to meet, until the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Surviving are York manuscripts numbers 1, 2, 4 and 5 (3 missing), the Hope manuscript, and the Scarborough manuscript, which turned up in Canada. Of these, York 4 has been the subject of controversy since it was first described in print. It is dated 1693, and was the first of the Old Charges discovered to have a separate Apprentice Charge, or a set of oaths specially for apprentices. The controversy was caused by the short paragraph describing how the oath was to be taken. “The one of the elders takeing the Booke / and that hee or shee that is to be made mason / shall lay their hands thereon / and the charge shall bee given”. Woodford and Hughan had no particular problem with this reading, believing it to be a copy of a much older document and realising that women were admitted to the guilds of their deceased menfolk if they were in a position to carry on their trade. Other writers, starting with Hughan’s contemporary David Murray Lyon, the Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of Scotland, insisted that the “shee” must be a scribal error for they, or a mistranslation of the Latin illi (they). Hughan failed to point out that the four lines in question are written in a competent hand in letters twice the size of the surrounding text, but riposted to Lyon that the Apprentice charge in York No 4, Harley manuscript 1942, and the Hope manuscript outline the apprentice’s duties to his master or Dame. Modern opinion seems resigned to letting York Manuscript number 4 remain a paradox.

Melrose No 2 (c1674)

The Lodge of Melrose successfully ignored the Grand Lodge of Scotland for a century and a half, finally joining in 1891 as the “Lodge Of Melrose St. John No 1bis”. The original Melrose constitutions are lost, but a copy was made in 1674 by Andro Mein (Andrew Main). He appended a copy of a certificate issued to an apprentice by “his master frie Mason, in the Year of our Lord 1581, and in the raign of our Soveraign Lady Elizabeth the (22) year”. Two other Scottish constitutions, the Kilwinning and the Aberdeen, declare that masons are liegemen of the King of England. This suggests an English origin of at least some of the Scottish Old Charges.

Printed constitutions

As the first Grand Lodge gathered momentum, the Rev. James Anderson was commissioned to digest the “gothic constitutions” into a more palatable form. The result, in 1723, was the first printed constitutions. While manuscript constitutions continued to be used in unaffiliated lodges, their condensation into print saw them die out by the end of the century. Anderson’s introduction advertised a history of Freemasonry from the beginning of the world. The York legend was therefore still employed and persisted through reprints, pocket editions, and Preston’s Illustrations of Freemasonry. Anderson’s regulations, the second part of the book, followed on a set of charges devised by George Payne during his second term as Grand Master. Both charges and regulations were geared to the needs of a Grand Lodge, necessarily moving away from the simplicity of the originals. When a new Grand Lodge sprang up to carry the older rite, which they saw as abandoned by the “Moderns”, their constitutions had a different approach to history. Ahiman Rezon parodied the old history of the craft and Anderson’s research. The charges and regulations of the Antients were derived from Anderson by way of Pratt’s Irish Constitutions. Almost inevitably, the legendary history disappeared after the union of the two Grand Lodges in 1813.

Rituals

While over 100 manuscript ‘constitutions’ exist, documents detailing actual ritual are much rarer. The earliest, dating from 1696, is the Scottish Edinburgh Register House manuscript, which gives a catechism and a certain amount of ritual of the Entered Apprentice and a Fellow Craft ceremonies. It was named after the building in which it was discovered, which houses the Scottish National Archives. The Trinity College Manuscript, discovered in Dublin, Ireland, but which is clearly of Scottish origin, has been dated to c.1710 and is substantially the same in content. The recently discovered Airlie manuscript (1705) is therefore the second oldest known Scottish stonemasons’ ritual. Although referred to as rituals, these manuscripts are also aide memoires, or ‘prompt sheets’. They therefore have three functions but for ease of reference they are commonly described as ‘rituals’. The significance of these three rituals lie in the fact that they; are of Scottish origin, are based on the ceremonies used by Scottish stonemasons; and that they pre-date the existence of any Grand Lodge. Collectively they are known as the ‘Scottish School’.

Edinburgh Register House MS (c1696)

Presumed to be from a lodge of operative masons, this document contains many features of speculative ritual. Hailed as the world’s oldest masonic ritual, the Edinburgh Register House manuscript of 1696 starts with a catechism for proving a person who has the word is really a mason. Among other things, the person seeking entry is expected to name their lodge as Kilwinning, attributing the origin to Lodge Mother Kilwinning in Ayrshire. The first lodge is ascribed to the porchway of King Solomon’s Temple and the form of the lodge outlined in a question and answer session, the form of the answers often being highly allegorical. A fellow craft is further expected to know and explain a masonic embrace called the five points of fellowship. The second half of the document describes all or part of an initiation ritual as the “form of giveing the mason word”.

Airlie Manuscript (c1705)

The Airlie manuscript was discovered in 2000 by Dr Helen Dingwall whilst undertaking unrelated research in Edinburgh Register House (which gave its name to the manuscript ritual referred to above) in the National Archives of Scotland. Of all the manuscripts of the Scottish School, only the origins of the Airlie manuscript (1705) are known with certainty. It is named after the family who owned it – the Earls of Airlie. Because the ownership and therefore the location of the manuscript is known it is of immense importance in understanding the origins of Freemasonry before the Grand Lodge era (from 1717). The Airlie manuscript has been analysed and discussed in considerable detail in Ars Quatuor Coronatorum (AQC), Vol.117.

Trinity College, Dublin

Other manuscripts from Scotland and Ireland give early ritual that largely confirm the text of the Edinburgh Register House manuscript. They differ mainly in having the giving of the Mason Word as the first part of the text, followed by the catechism of the first and second degrees in the form of questions and answers. These include the Chetwode Crawley, the Kevan, and the Trinity College manuscripts. In the Trinity college text the Mason Word is actually written down as “Matchpin” and appears to be part of an early Master Mason’s degree. The Chetwode Crawley manuscript, although discovered in Dublin, refers in its catechism to the Lodge of Kilwinning, clearly demonstrating that it is of Scottish origin and is therefore part of the Scottish School referred to above.

The Haughfoot fragment (c1702)

Haughfoot was a hamlet, consisting mainly of a staging post for horses and carriages, in the Scottish Borders near the village of Stow. It was in this unlikely location that a lodge was founded in 1702 by men who were mainly local landowners. The significance of this lodge lies in the fact that none of its members were stonemasons, confirming that modern Freemasonry was fully evolved in Scotland before the appearance of centralised authority in the form of Grand Lodges. The minute book of the lodge, which is extant, commences in 1702 and inside the front covers is the part which is identical to the last portion of the Edinburgh Register House and Airlie manuscripts. Although not complete (the missing part was almost certainly removed for reasons of secrecy) the Haughfoot fragment is sufficient to confirm that it was very likely to have been identical to the two previously mentioned manuscripts. The ‘fragment’ was probably retained because the minute of the first meeting of the Lodge commences immediately after this portion of ritual on the same page.

Graham Manuscript

The Graham Manuscript, of about 1725, gives a version of the third degree legend at variance with that now transmitted to master masons, involving Noah instead of Hiram Abiff. The Graham Manuscript appears to have been written in 1726 and obvious scribal errors within it indicate that it was copied from another document. It turned up in Yorkshire during the 1930s, but its exact origin is unknown, Lancashire, Northumberland or South Scotland being suggested. The document is headed The whole Institution of free Masonry opened and proved by the best of tradition and still some reference to scripture, There follows an examination, in the form of the sort of question and answer catechism seen in the earlier rituals. In what appears to be the examination of a Master Mason, the responder relates what modern masons would recognise as that part of the legend of Hiram Abiff dealing with the recovery of his body, but in this instance the body is that of Noah, disinterred by his three sons in the hope of learning some secret and the mason’s word is cryptically derived from his rotting body. Hiram Abiff is mentioned, but only as Solomon’s master craftsman, inspired by Bezalel, who performed the same function for Moses. The tradition of deriving freemasonry from Noah seems to be shared with Anderson (see above). Anderson also attributed primitive freemasonry to Noah in his 1738 constitutions.

Minutes

The second Schaw Statutes of December 1599 having made it compulsory for Scottish lodges to have a secretary, early documentation there is rich in comparison with England, where actual minutes start in 1712 in York and 1723 in London. Records for the Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary’s Chapel) No.1 extend back to the sixteenth century. Minutes from the Premier Grand Lodge of England, the Antient Grand Lodge of England, and the Grand Lodge of All England meeting at York trace the organisational development and rivalries within eighteenth century English Freemasonry.

Aitchison’s Haven

The oldest minute book discovered is that of Aitchison’s Haven, a location just outside Musselburgh, in East Lothian. The first entry records Robert Widderspone being made Fellow of Craft on 9 January 1598.

Mary’s Chapel

The records of the Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary’s Chapel) No.1 extend back to 1598, making them an important historical source as the longest continuous masonic record. David Murray Lyon’s history of the lodge, published in 1873, mined the records of Edinburgh’s oldest lodge and produced a history of Scottish Freemasonry. The first entry, on 28 December 1598, is a copy of the first Schaw statutes. The next year, on the last day of July, the first proper minute records disciplinary proceedings against a member who employed a cowan, or unqualified mason. The first entries are terse and not always helpful, expanding as successive secretaries became more conscientious. The records trace the development of the lodge from an operative to a speculative society.

York

The minutes of the old lodge at York, which later called itself the Grand Lodge of All England, give a glimpse of masonry outside the Grand Lodges of the period. The minutes are erratic, with spaces of some years between some entries. It is often impossible to tell if the minutes are lost, were never taken, or the lodge did not meet at all. They do, however, contain the full text of a speech by the antiquary Francis Drake in 1726, in which he discusses the contemplation of geometry and the instructive lectures which ought to be occurring in lodges. He used the York legend to claim precedence of his own lodge over all others in England and being a more careful historian than the compilers of the Old Charges, Edwin the son of Athelstan became Edwin of Northumbria, adding three centuries to his lodge’s pedigree. Later minutes show the lodge adding ritual and developing a five degree system from a single ceremony where a candidate was admitted and made a Fellow Craft in one evening. The York account of the split between the Premier Grand Lodge of England and the Lodge of Antiquity provides a balance to the charged prose of William Preston. The minutes cease for the final time in 1792.

London Grand Lodges

Minutes of both of the Grand Lodges which finally formed the United Grand Lodge of England are preserved in their archives. Plans by Quatuor Coronati Lodge to publish them all were interrupted by the First World War and only one volume was published, covering the minutes of the Premier Grand Lodge of England from their first minutes in 1723 to 1739. The first of five volumes of Grand Lodge minutes contained three lists of subscribing lodges and their members, dating from 1723, 1725 and 1730. The lodges are first numbered in John Pine’s engraved list of 1729. All three manuscript lists have had lodges added after their compilation, but in spite of this they still trace the development of the first Grand Lodge during a critical period in its development, as it moved from being an association of London lodges to a national institution. No further lists were included in the minutes. They start on 24 June 1723 with the approval of Anderson’s constitutions and the resolution that no alteration or innovation in the “Body of Masonry” could occur without the approval of Grand Lodge. The Earl of Dalkeith was then elected as the next Grand Master, but his chosen deputy, John Theophilus Desaguliers, was only approved by 43 votes to 42. After dinner the outgoing Grand Master, the Duke of Wharton, asked for a recount. This being refused, he walked out. Many such human touches are revealed in the minutes, together with the beginnings of masonic charities and discipline of masons and lodges. There are no minutes for the year 1813 and only rough notes from the Antients, leaving a gap in the run-up to union that must be spanned from other sources.

The first meetings of the Antients, as they came to be known, are also missing, but these span only a few months instead of the six years of silence from the older institution. On 5 February 1752 Laurence Dermott became Grand Secretary and proper minutes ensued. Although these have still to be published, they have been extensively mined by masonic writers, particularly Bywater’s biography of Dermott, which draws verbatim from the minutes. Dermott’s style is quirky, occasionally obtuse and often full of dry humour. Discipline is a frequent subject, collecting dues from delinquent lodges and the “leg of mutton” masons who admitted men to the Holy Royal Arch for the price of such a meal without the least idea what the actual ritual was and claimed to teach a masonic technique for becoming invisible. The conflict between the two Grand Lodges, while obvious from other contemporary sources, is largely absent from both sets of minutes.

Other Masonic documents

Fabric Rolls of York Minster

Records of the operative lodge at York Minster are included in the rolls relating to the ‘fabric’ (the building material) of the construction, starting with an undated entry from about 1350–1360, and ending in 1639. Written mainly in Latin until the Reformation, they comprise accounts, letters, and other documents relating to the building and maintenance of the church.

Statutes of Ratisbon

The Statutes de Ratisbon were first formulated on 25 April 1459 as the rules of the German stonemasons, when the masters of the operative lodges met at Ratisbon (now Regensburg). They elected the master of works of Strasbourg Cathedral as their perpetual presiding officer. Strasbourg was already recognised as the Haupthütte, or Grand Lodge of German masons. The General Assembly was held again in 1464 and 1469 and the statutes and society were approved by the Emperor Maximilian in 1498. The final form of the statutes regulated the activity of master masons (Meister), with an appendix of rules for companions or fellows (Gesellen) and apprentices (Diener). These regulations were used for over a century as the Strasbourg lodge operated as a court for the settlement of building disputes. This ended in abuse of power, and the Magistrates removed the privilege in 1620. Strasbourg was annexed by France in 1681 and its rule over German operative lodges interdicted at the beginning of the 18th century. While there seems little likelihood that the code affected the emergence of German speculative lodges in the 18th century, they may have had some influence on a few of the English “charges”.

Other German ordinances are found in the Cologne records (1396–1800), the Torgau ordinances of 1462 and the Strasbourg Brother-book of 1563. The Cologne guild comprised both stonemasons and carpenters and was repeatedly referred to as the Fraternity of St. John the Baptist.

Schaw Statutes

William Schaw was master of works to King James VI of Scotland and was also the general warden of all the lodges of Scottish stonemasons. This meant he was in charge of the erection, repair and maintenance of all government buildings and also the running of what was already a fraternity of masons, who ensured that all building work was undertaken by properly qualified persons and also provided for their own sick and the widows of their members. Schaw formalised the working of the lodges in two sets of statutes, set down on 28 December 1598 and 1599. Many now see these as the beginnings of modern Freemasonry. Robert Cooper, the archivist and writer, goes so far as to call Schaw the Father of Freemasonry.

The Schaw Statutes were issued from Edinburgh, where Schaw seems to have met with representatives of lodges from central and eastern Scotland to formulate these regulatory principles. The 1598 Statute enjoined masons to be true to one another and live charitably together as becomes sworn brothers and companions of the craft. This shows that there was already an oath involved and invoked the legal definition of a brother as one to whom another was bound by oath. There followed directives as to the regulation of the craft and provisions for the masters of every lodge to elect a warden to have charge of the lodge every year and that the choice be approved by the Warden General. An apprentice had to serve seven years before being received into a lodge and a further seven before becoming a fellow in craft, unless by consent of the masters, deacons and wardens and after examination. The term Entered Apprentice is used for an apprentice who has been admitted to the lodge. The document was circulated to every lodge in Scotland, which caused some degree of upset in Kilwinning. The lodge in Kilwinning claimed to be the oldest lodge in Scotland and was insulted not to have been represented. They sent Archibald Barclay to a further meeting in 1599, from which issued the second Statute, again on 28 December. In an attempt to paper over the crack created by the first meeting, Edinburgh was declared the first and principle lodge, Kilwinning the second and head lodge. Stirling came third. Kilwinning was given charge of the West of Scotland and charged to examine their masons in “the art of memory”, with fines prescribed for failure. What is being remembered is unspecified, but evidently known to all the masons present. Schaw also insisted that each lodge employ a notary, which resulted in the Scottish lodges starting to keep minutes. The document ends by thanking Archibald Barclay, and looking forward to obtaining the King’s warrant for the statutes. Kilwinning, far from being appeased, took no further part in the dealings of Schaw’s lodges.

Kirkwall Scroll

The Kirkwall scroll is a floor cloth which contains many masonic symbols, many more opaque images and cryptic writing which may either be a code or badly painted Hebrew. It hangs on the west wall of the temple of Lodge Kirkwall Kilwinning No. 38(2) in Orkney, but is too long to be completely displayed. It is 18 ft 6in long and 5 ft 6in wide, and is composed of a full-width central strip stitched at each side to two half-width side strips. The left border appears to show the wanderings of the Israelites before they arrived in Egypt and reads from top to bottom. The right shows their wanderings in the wilderness after the Exodus, with the route marked in years from 1 to 46 and branching many times at the end. The central cloth contains seven painted scenes and tableaux. The bottom scene shows an altar flanked by two pillars, all surrounded by more or less familiar masonic symbols. Working upwards, the second has an altar surrounded by a different set of symbols, the third has the altar and pillars together with the cherubim present on the arms of the Antient Grand Lodge of England, the Grand Lodge of Ireland and the United Grand Lodge of England. Above this is a schematic of the tabernacle of the Ark of the Covenant, followed by what may be the last judgement. The sixth shows a cross atop a pyramid, surmounted by a rainbow, surrounded by masonic and alchemical symbols, and at the top a naked woman, assumed by early authors to be Eve, sitting under a tree surrounded by animals. In the distance is a sea or lake full of fish and beyond this are mountains. The whole is painted in oil, mainly in pale blue. In the top tableau the woman, fish and animals are pink, the sea green and the tree and mountains brown.

Lodge minutes of 27 December 1785 state; – “Bro. William Graeme, visiting brother from Lodge no 128 Ancient Constitution of England was at his own desire admitted to become a member of this Lodge and he accordingly signed the articles and Rules thereof”. Seven months later he donated a floor cloth to the lodge, now generally assumed to be the Kirkwall Scroll. Archivist and Masonic historian Robert Cooper has presented evidence arguing that the scroll was made by William Graeme, or under his direction and he dates it to the latter part of the 18th century on the basis of a detailed analysis of its symbolism.

Cooper’s contribution was in response to claims of mediaeval origin for the scroll. Andrew Sinclair, a leading proponent of Freemasonry’s descent from the Knights Templar, hailed it as a great mediaeval treasure, comparable with the Mappa Mundi in Hereford Cathedral. His claim arises from what opponents describe as an optimistic reading of radiocarbon dating and creative interpretation of the panels. The Tabernacle is claimed to be King Solomon’s Temple, with the tents removed in Sinclair’s reproduction. Sinclair and his supporters also have trouble with lodge 128 of the Antients. It is variously claimed to be in Yorkshire, or Prince Edwin’s Lodge in Bury (a Moderns Lodge constituted in 1803). In 1785, 128 was meeting in the Crown and Feathers, Holborn, London. Robert Lomas, a supporter of the early dating, now sees part of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite in one of the altar inscriptions and much of the symbolism. This would place the document to the second half of the Eighteenth century in a conventional history of the Rite, but Lomas believes it to be mid-fifteenth, again based on radiocarbon dates, which make the side panels younger than the central strip. Realistically, agreement on the scroll, its context and symbolism is a long way off.

In Summary:

Anderson tells us, in the second edition of the Book of Constitutions, that in the year 1719;

“at some private Lodges several very valuable manuscripts concerning the Fraternity, their Lodges, Regulations, Charges, Secrets, and Usages, were too hastily burnt by some scrupulous Brothers, that these papers might not fall into strange hands.”

Fortunately, this destruction was not universal. The manuscripts to which Anderson alludes were undoubtedly those Old Constitutions of the Operative Masons, several copies of which, that had escaped the holocaust described by him, have since been discovered in the British Museum, in old libraries, or in the archives of Lodges, and have been published by those who have discovered them.

These are the documents which have received the title of “Old Records,” “Old Charges,” or “Old Constitutions.” Their general character is the same. Indeed, there is so much similarity and almost identity, in their contents as to warrant the presumption that they are copies of some earlier document not yet recovered.

The earliest of these documents is a manuscript poem, entitled the Constitutiones artis geometriae, secundum Eucleydem, which is preserved in the British Museum and which was published in 1840 by Mr. Halliwell, in his Early History of Freemasonry in England. The date of this manuscript is supposed to be about the year 1390. A second and enlarged edition was published in 1844.

The next of the English manuscripts is that which was published in 1861 by Bro. Matthew Cooke from the original in the British Museum, and which was once the property of Mrs. Caroline Baker, from whom it was purchased in 1859 by the Curators of the Museum. The date of this manuscript is supposedly c1490.

All the English Masonic antiquarians concur in the opinion that this manuscript is next in antiquity to the Halliwell poem, though there is a difference of about one hundred years in their respective dates. It is, however, unlikely that there were not other manuscripts in the intervening period. But as none have been discovered, they must be considered as non-existent and it is impossible even to conjecture, from any viewpoint, whether, if such manuscripts did ever exist, they shared more of the features of the Halliwell or of the Cooke document, or whether they presented the form of a gradual transmission from the one to the other.

The Cooke Manuscript is far more elaborate in its arrangement and its details than the Halliwell and contains the Legend of the Craft in a more extended form. In the absence of any other earlier document of the same kind, it must be considered as the underlying structure, as it were, on which that Legend, in the form in which it appears in all the later manuscripts, was moulded.

In the year 1815, Mr. James Dowland published, in the Gentleman’s Magazine, the copy of an old manuscript which had lately come into his possession, and which he described as being “written on a long roll of parchment, in a very clear hand, apparently early in the 17th century and was very probably copied from a manuscript of an earlier date.” Although not as old as the Halliwell and Cooke Manuscripts, it is deemed of very great importance, because it is chronologically sequential, apparently the earliest of the series of later manuscripts, so many of which have, in relatively recent years, been recovered.

Though not an exact copy, it is evidently based on the Cooke Manuscript. But the later manuscripts comprising that series, at the head of which it stands, so much resemble it in detail and even in phraseology, that they must be considered to be either copies made from it or, what is far more probable, copies of some older and common original, of which it also is a copy. The original manuscript which was used by Dowland for the publication in the Gentleman’s Magazine is lost, or can not now be found. But Mr. Woodford and other competent authorities ascribe the year 1550 as being its approximate date. Several other manuscript Constitutions, whose dates vary from the middle of the 16th to the beginning of the 18th century, have since been discovered and published, principally by the industrious labours of Brothers Hughan and Woodford in England, and Brother Lyon in Scotland.

All of the manuscripts cited above are of very similar format and begin, except the Halliwell poem, with an invocation to the Trinity. Then follows a descant on the seven liberal arts and sciences, of which the fifth, or Geometry, is said to be Masonry. This is succeeded by a traditional history of Masonry, from the days of Lamech to the reign of King Athelstan of England. The manuscripts conclude with a series of “charges,” or regulations, for the government of the Craft while they were of a purely operative character.

The traditional history which constitutes the first part of these “Old Records” is replete with historical inaccuracies, with anachronisms and even absurdities. Yet it is primarily valuable, because it forms the germ of that system of Masonic history which was afterward developed by such writers as Anderson, Preston, and Oliver from whose errors, the iconoclasts of the present day are successfully striving to free the Institution, so as to give its history a more rational and methodical form.

This traditional history is presented to us in all the manuscripts, in an identity of form, or, at least, with very slight verbal differences. These differences are, indeed, so slight that they suggest the strong probability of a common source for all these documents, either in the oral teaching of the older Masons, or in some earlier record that has not yet been recovered. The tradition seems always to have secured the unhesitating belief of the Fraternity as a true relation of the origin and the progress of Masonry and hence it has received the title of the “Legend of the Craft.”

From the zealous care with which many manuscripts containing this legend were destroyed in 1719 by “scrupulous brothers” who were opposed to its publication, we might believe that it formed a part of the esoteric instructions of the Guild of Operative Masons. If so, it lost this secret character by the publication of Roberts’s edition of the “Constitutions” in 1722.

In the earlier German and French Masonic records, such as the “Ordenung dey Steinmetzen” at Strasburg in 1462, and the “Reglements sur les Arts et Metiers” at Paris in the 12th century, there is no appearance of this legend. But it does not follow from this that no such legend existed among the French and German Masons. Indeed, as it is well known that early English Operative Masonry was derived from the continent, it is natural to suppose that the continental Masons did indeed bring the legend into England.

There is internal evidence to be found in the English manuscripts of both French and German interpolations. The reference in the Legend to Charles Martel connects it with the French Masonry of the 12th century and the invocation to the “Four Crowned Martyrs” in the Halliwell Manuscript is undoubtedly of German origin.

The importance of this Legend in the influence that it exerted for a long period on the Craft as the accredited history of the Institution makes it indispensably necessary that it should form a part of any works that profess to further disclose of the history of Masonry.

![]()