York, the county seat of Yorkshire, is one of the oldest cities in England, and one of the most famous cities in the world, next after London itself.

Speculative Freemasonry’s Mother City, it is also the great Masonic city. The Britons had a town on its site before the Roman occupation; the Romans themselves established a barracks there, and later organized the town and its environs as a colonial or municipality. It was for years the home of King Athelstan. When its Paulinus was made Archbishop in 627 A.D., it became the seat of an Archbishopric which ever since has ranked second in importance only after Canterbury.

Alcuin of York was selected by Charlemagne as the teacher of himself and his sons (about 800 A.D.) because the cloister school of which Alcuin was head was so renowned, and because York itself was the Oxford of that day, and scarcely less known on the Continent than in England itself. The War of the Roses, “England a most terrible war,” was fought between Yorkists and Lancastrians. It also had for some two centuries a primacy in the fine arts, and more Gothic architecture was crowded into its limits than in any other centre; its Minster is one of the sublimest structures ever built anywhere, or for any purpose. Its fame as a Masonic city rests on many foundations:

1. A Bishop of York attended the Council of Arles in 314 A.D., and the Council Records indicate that he was given precedence over the Bishop of London; such a Bishop must have had a Bishop’s church, or cathedral, and it is likely therefore that York began to be a centre of architecture and of its sister arts and attendant skilled crafts as early as the Fourth Century.

2. Had Athelstan’s name never been mentioned in the Old Charges he would have a large place in Masonic history because he was a King of Operative Freemasonry as well as King of England. York was Athelstan’s home. He built or rebuilt many structures there, and it is probable that the city already had its guildhall, and very probably what later would be caned a City Company of Masons. Also, he built and rebuilt much in London, and was so interested in the work personally that rules and regulations for craftsmen bulked large in his laws and edicts. Also, he was a city builder, a role to which even kings are seldom admitted, for while Exeter had been a Welsh City before him, he moved the Welsh out and in their place built a new city according to a plan of his own. When the Old Charoes attribute to Athelstan a great interest in Freemasonry and a great love for Freemasons they do not exaggerate- indeed, they fall short of the whole truth because apparently the author of the Old Charges knew nothing of Athelstan’s work outside of York.

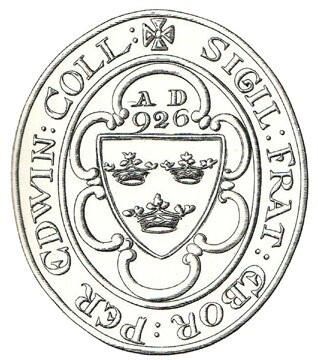

3. In one version of the Old Charges it is stated that at an Assembly of Freemasons in York in 926 A.D., Athelstan gave the Craft a Royal Charter, a document which carried in itself a higher authority than one issued by either the Church or any lord of lesser degree or any city; the other versions of the Old Charges say that Athelstan had been titular head of the Fraternity of Freemasons, but had made over his title and prerogatives to a son, Prince Edwin. Historians question this tradition bed cause, first, it is unsupported by contemporary records; second, because no trace of a son of Athelstan named Prince Edwin has ever been found; third, no trace of the Charter itself, either in a copy or in quotation, has been discovered, although it is reasonable to think that the Freemasons would have preserved many copies of a document so important to themselves.

Gould questioned the tradition because he did not believe that General Assemblies of the Craft had ever been held, but his argument is dubious because if the Craft had not held assemblies a number of kings would not have issued edicts to prohibit them (see in this Volume, under Wycliff it is dubious in the case of Athelstan also because Gould apparently did not know what was insane by an ‘assembly.”

It is possible to reinterpret the whole problem of the Assembly at York and of the Royal Charter said to have been granted there, and to do so without stretching the evidence. Athelstan himself (and not through an agent) was a direct employer of Freemasons at York, at London, at Exeter, and doubtless elsewhere; that which was a written contract at the time may have come to be thought of as a charter afterwards. Also, as stated above, Athelstan himself drew up rules and regulations for the Freemasons, and incorporated them in h s written laws- in so doing, and also while acting as an employer, both his own laws and contracts would specifically approve, at least by implication, the Freemasons’ own rules and regulations. If these reasoning’s be sound, the tradition of a Charter granted by Athelstan becomes true in substance if not true in form and for the Freemasons had the same point.

4. The first permanent Lodges were established about 1350 A.D. According to both civil and ecclesiastical law at the time such a body had to have a charter; it also had “to make returns,” that is, to report their rules and regulations and their membership to the civil authorities. It is reasonable to believe that the Old Charges were written partly for each of these purposes.

If it be objected that the Old Charges are not a charter, but only the claim that Athelstan had already granted them a Royal Charter long before, the fact only proves that the Freemasons themselves in 1350 A.D. relieved literally in the “York tradition” but what idling this connection far more important (Gould and Mackey both overlooked that importance), the chit authorities themselves believed it, and permitted the permanent Lodges to continue to work under the Old Charges. Had those civil authorities disbelieved it, they would have rejected the Old Charges and compelled the Lodges to seek civil charters.

Belief in the York tradition, and for whatever it may be worth, rests not on a modern theory about a supposed event a thousand years ago, but on a belief held by both Freemasons and civil authorities in the Fourteenth Century. The latter were four centuries removed from Athelstan, but that was not then as wide a gap in time as it would be now (when change is at least fifty times as rapid) because in the Middle Ages written official documents were preserved with great care; and this is especially true of York, as readers of Sir Francis Drake have discovered.

5. The Fabric Rolls of York Minster published in by the Surtee’s Society (Durham 1859) we learn that in 1509 there were two Craft Lodges at York in existence, and the Historian Kugler says in his “Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte”, that in the 12th and 13th century near York a school of Architecture was in existence.

6. There was a Old Grand Lodge in York, no doubt of a predominantly Speculative membership, before the Grand Lodge was erected in London in 1723; how old it was there is no way of discovering, but it is on record as early as 1705 A.D. According to its own Minutes it was sometimes called a Grand Lodge, and sometimes a General Lodge —by this later term it was probably meant that it had set up daughter Lodges. In 1725 A.D. the Old Grand Lodge of York Grand Lodge of All England.”

7. When a group of London Lodges set up in 1751 A.D. that Grand Lodge which everywhere was to become famous as the Ancient Grand Lodge, its appeal to English Masons who already had two Grand Lodges was based on its claim to recover and to preserve “the Ancient Customs;” these customs it attributed to the York Grand Lodge.

Both R. F. Gould and Wm. J. Hughan stigmatized this use of “York” as an “Americanism. ” How could it have been when it originated in York itself, in the London Grand Lodge of 1751, A.D., and came to the American Colonies via Canada? Moreover it is only in popular and uncritical usage that “York Rite” is employed in America; the doctrine that Freemasonry originated in York has has been officially adopted.

The great work on York is the one entitled Eboracum, a thick tome of amazing erudition, written by the above-mentioned Bro. and Dr. Sir Francis Drake. It is a huge volume in fine print, almost suffocatingly packed with facts.

Any beginning Masonic researcher could look far for a better specialty it is a mine for Masonic essayists: in it countless old customs and symbols preserved in Freemasonry appear in the form of records or minutes made at the time of their use.

![]()